Jeremy debates Campus Progress

August 25th 09:31:05 AM

Background:

Dana Goldstein of Campus Progress was a co-panelist with Jo Jensen at the recent C-span event. Dana wrote an account of the event that I did not feel was fair, and I told her so in a comment at the bottom of her article. Her response to my comment is located here where she challenges me to disprove the statement, "I would like to see you, or any other young pro-privatization activist, respond to the basic facts I've outlined: every American earning more than $20,000 per year would see a decrease in Social Security benefits under conservative private account proposals."

So I took her up on her offer, which you can read by clicking "read more".

I will give her a few days to respond, and then I will pose a question to Campus Progress to answer.

UPDATE: I'm not sure where Campus Progress is. It's been a week, and I haven't heard anything or seen anyone from there posting in any of the threads. JR is making an effort to fill in, but he really shouldn't have to. Where are they?Assumptions and Methodology

Alright. In order to do this right, we've got to agree on some sources. I assume that you guys would have no trouble with citing the CBO (cbo.gov), the Social Security Administration (including the trustees report), and the Congressional Research Service (crs.gov), so I will limit all of my facts and figures to these organizations.

Second, I need to be clear in defining the scope of what I am responding to. You ask that I answer the question: I would like to see you, or any other young pro-privatization activist, respond to the basic facts I've outlined: every American earning more than $20,000 per year would see a decrease in Social Security benefits under conservative private account proposals

I immediately see a problem with the question (every personal account proposal is different), but I will narrow it in your favor for the sake of argument. I doubt you would have any objection to using President Bush's plan for analysis. But I must be clear that S4 does not advocate in favor of any particular plan. There are a lot of them out there, with various benefits and drawbacks, and to define personal accounts as “Bush's Plan" is to oversimplify.

Secondly, let me add that the question you posed illustrates, more than any other, your unwillingness to talk honestly about this issue rather than engage in statistics manipulation and rhetoric. Now, I have no idea where you got this number from (because the article you linked as your source doesn't even have the number 16 in it anywhere), but I can take a guess at how you might try to come up with it. Tell me if i'm wrong.

You simply ignore the fact that by design one trades promised benefits from Social Security for the opportunity to gain a higher return in the market. By doing this you can say "They're cutting your 'guaranteed' benefits by X%". You are merely stating that a "16% guaranteed benefit reduction" is a "16% guaranteed benefit reduction"—or put differently, restating a small part of a PRA proposal as the whole proposal so that you can shoot it down (otherwise known as a straw man). So the relevent question is, "Will the rate of return in personal accounts be higher or lower than the rate of return from the current system?" And I will prove below that by any reasonable estimation, PRAs will perform at least equal to or better than current payable benefits.

Finally, what is the standard of comparison? I must admit that one of the things that bothers me about your analysis (not you personally, but the “anti personal account" crowd), is that when comparisons are made you use the promised benefit (what you call the "guaranteed" benefit, which I find curious since we're guaranteed to not get that amount, see the trustees report) instead of the payable benefit. According to the SS trustees report there is absolutely no chance of Social Security paying its promised benefits without changes. (deficit begins in 2017, “trust fund" is exhausted 2042). In fact, the report you cited appears to use promised benefits. I just don't think that's fair since the promised benefits might as well be pulled out of thin air if we can't pay them. So i'm going to use payable benefits.

Analysis

Now, looking at this CRS report on President Bush's proposal, we see that the rate of return of the PRAs depends on the real (after inflation) return of the assets in them. Now, the social security actuaries have predicted that the average return over one's lifetime would amount to 4.6% per year after inflation. Of course we have to account for fluctuations from this figure, but I find it puzzling why the author of the report you cited decided to choose the 3% figure as the “baseline". Wouldn't the baseline be what the actuaries have forecasted (since, by definition, a forecast is the point at which events on either side are equally likely)? The 3% figure is our minimum target, not our baseline.

So to really be fair, i'll use the three rates of return in your linked analysis (1.5, 2.7, and 4.6), with the note that it's entirely possible that returns could be higher than 4.6% (in fact, according to this NYU page, during the period 1965-2005 the nominal rate of return for stocks and long term bonds has been 10.26% and 7.05%, respectively.

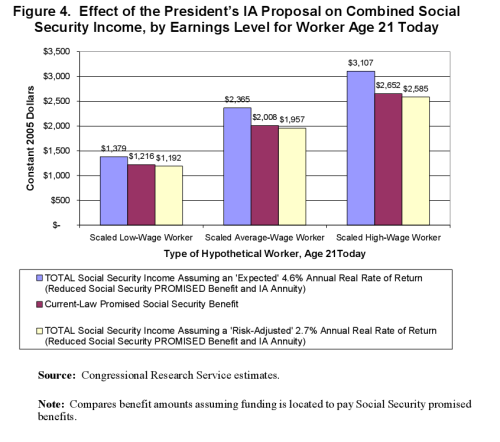

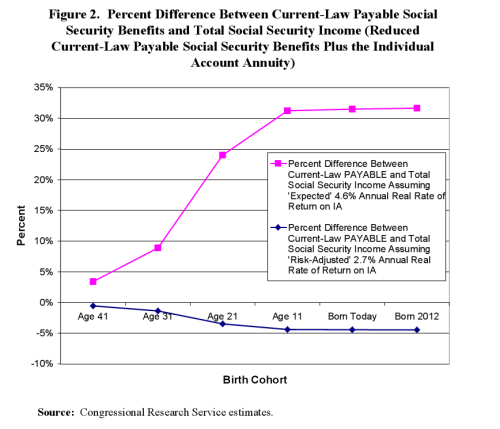

The graph below (from this CRS report , page 18) shows two of the rates (4.7 and 2.7) as compared with the promised benefits. You can see that even the risk adjusted scenario (in other words, the risk we took on the accounts gained us nothing), the personal account only comes in, at 3% below the promised benefits...with an actuarial projected return of 13% better than promised benefits.

*Click on the graphs to enlarge

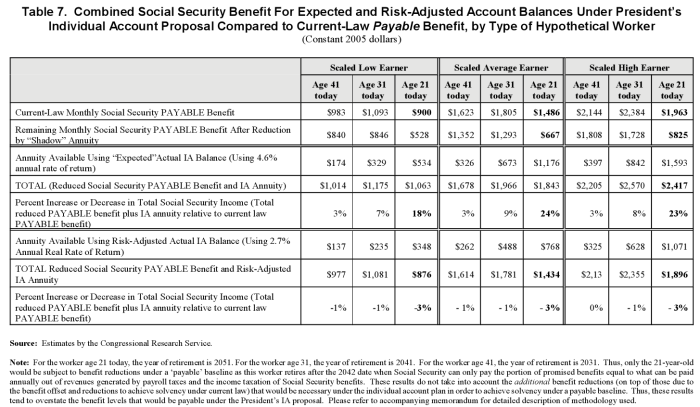

The results get even better when one compares the potential rates of return with payable benefits in the same CRS report, page 27. Under these calculations, the potential rate of return is 18% higher under the actuaries' projected numbers for a 21 year old low income earner...24% for an average earner.

Also:

Even according to your own numbers here in the event of a catastrophic (and highly unlikely) real rate of return of 1.5%, the proposal only comes in 14% under the current promised benefits... which I might add again there is no way we can pay promised benefits under the current system.

In sum, I can see no reasonable interpretation of the numbers (meaning one includes both the benefits from the current system and also the additional income from the PRA annuity) where one could make a blanket statement that “every American earning more than $20,000 per year would see a decrease in Social Security benefits under conservative private account proposals".

Note: Our spam filter for wordpress isn't working correctly, so I am having to manually approve all of the comments. So your comment may not appear for several hours.

Posted by Jeremy Tunnell

Comments

I certainly don't want to put myself up as the spokesperson for CP (since I'm neither employed there, nor a party to this challenge between you and Dana), so thoughts are my own, and since I'm somewhat pressed for time, I can only pick some points for discussion.

I note that in discussing likely returns on investments, you used one hell of a long timeframe to establish an average return (1965-2005, from the NYU page). In that same time period, there were more dips and downturns than I can shake a stick at.

Considering that the primary purpose of SocSec is to provide a cushion for retirement, and considering that "among elderly Social Security beneficiaries, 54% of married couples and 74% of unmarried persons receive 50% or more of their income from Social Security. Among elderly Social Security beneficiaries, 21% of married couples and about 43% of unmarried persons rely on Social Security for 90% or more of their income," according to the SSA http://www.ssa.gov/pressoffice/basicfact.htm , how are we supposed to reconcile the fact that the "security" aspect of Social Security is inherently jeopardized by the nature of privatization, especially in an age where market shocks can come at any time and have an immediate and massive impact (such as terror attacks, big effin' hurricanes, etc.)? Does privatization have a chance of maintaining the level of security currently provided for that majority of retirees that rely on SocSec to, you know, eat and pay for housing? Or should we really just be looking for solutions to keep the program solvent in a form as close to its current one as possible, if the purpose behind it is to be maintained?

Posted by JR on August 18th 12:47:46 PM

I note that in discussing likely returns on investments, you used one hell of a long timeframe to establish an average return (1965-2005, from the NYU page). In that same time period, there were more dips and downturns than I can shake a stick at.

First, I added that statistic as an aside, and my core argument stands without it.

Second, my point is precisely that it doesn't matter how many ups and downs are in the market...only what the lifetime return on investment is.

The hard facts are these: Even if someone invested every penny of their money in the stock market in 1887 and had to withdraw it in 1932, at the bottom of the Great Depression, they would have still multiplied their investment 7-fold...earning about 4.3 percent/year. And that is the absolute worst case scenario in American history. (Source: In Our Hands, Murray, 2006)

Posted by jeremy on August 20th 10:29:26 PM

And those are adjusted numbers?

Posted by JR on August 20th 11:53:56 PM

Test

Posted by noid on August 21st 01:33:22 AM

The numbers appear to be nominal numbers.

So you would need to adjust them by the average inflation rate, which, according to this page hovered around 1% except for 1917-21

Posted by jeremy on August 21st 06:21:59 PM

From my glance at 1965-2005, it seems like we're talking about an average inflationary rate of around 6.32% (I may be doing that math wrong--I'm not sure that the base year is 1965. Even if it is a little off, though, we can probably agree that inflation was no laughing matter, especially in the mid-late 70s).

Those NYU numbers were likewise nominal. That would place the average return for stocks and long-term bonds, adjusted for inflation, at 3.94% and around 3/4ths of a percent, respectively.

Inflation makes these numbers hard to calculate accurately, as the dollar you invested in a long-term bond in 1965 was worth a much different amount than the dollar invested in 1985 or 2004, and those dollars would obviously be gaining less interest in long-term bonds. Still, and this is likely a result of my being rusty in the field (I dropped my econ dual major in 2003 to focus more on political science), I'm not sold on the numbers.

Posted by JR on August 23rd 06:29:30 PM

By my calculations from the inflation history page (http://eh.net/hmit/inflation/), I get 4.63% as the average inflation rate from 1965-2005.

Then according to the NYU numbers, that would put the real return for stocks and bonds at 5.63% and 2.42%, respectively.

Plugging that into the CRS analysis puts us a whole percentage point ahead of the Trustee's 4.6%, meaning that an investor with a PRA starting in 1965 would come in on the order of 20%-30% better than the current system. (ignoring dollar-cost-averaging).

Even if the person chose to invest in 100% bonds, they would still come out slightly better than the promised benefits under the current system.

Posted by jeremy on August 23rd 11:00:43 PM

I guess Dana nor anyone else from Campus Progress have anything to say about Jeremy’s analysis. I was hoping to see someone respond to his comments. I guess Dana and Campus Progress agreed with his analysis. Are they (Campus Progress) just going to be like Congress and ignore the issue all together? I guess so.

Posted by Jason on August 24th 04:32:20 PM

Now, correct me if I'm wrong, but we've gotten down to an average of only one point higher performance for private accounts over SocSec once the figures are adjusted for inflation, ignoring dollar-cost-averaging. Have we yet factored in administrative cost increases for overseeing over two hundred million individual funds instead of one single-payer fund?

Posted by JR on September 01st 07:49:59 PM

I'm not sure where you get the "average of one point higher". If we follow the trustees predictions we're looking at about a 1.6% better return per year.

Now that doesn't sound like much, but we're talking about compound interest.

If you invested $10,000 for 40 years, without making another deposit, the principal would grow to $32,620.38 at 3% interest, but it would grow to $60,432.06 at 4.6% interest. I wouldn't say a difference of roughly double is worth dismissing.

Regarding management fees, it has been said many times that PRAs would be modeled after the Thrift Savings Plan, where management fees average $26/year (Source)

And PRAs would only use Index Funds, which historically have astronomically low management fees.

Posted by jeremy on September 05th 12:01:26 PM

Inflation numbers prior to the 1983 recession are meaningless. In the 1970's, four decades of Keynesian fiscal polices comibned with atrociously bad monetary politics combined to form a unique set of circumstances that led to double-diget inflation in the late 1970's.

In 1981, Paul Volker, who at the time was the new fed chairman (before Greenspan) raised interest rates to wring inflation out of the economy at any cost (i.e. a MAJOR recession). Following a terrible economic slowdown in 1982, inflationary expectations plummeted. Inflation, and thus Inflationary expectations, have never returned to their pre-1983 levels.

That is why all inflationary data pre-1982 is useless for predicting the future.

Aside: Personally, I'd consider any inflationary numbers prior to the 1995 soft landing useless, but reasonable people can differ on that one.

Posted by Cahnman on September 05th 07:03:19 PM

Yeah. Its utterly meaningless (and sophomoric) to attempt to predict future inflation by calculating inflation over some arbitrarily chosen past period.

Setting aside for a second the fact that economic history is not cyclical, these figures are not even giving you a real picture of what those past numbers would mean in adjusted terms. As people who understand the history of inflation measures (like Cahnman) will tell you, you can't even accurately describe past market performance with these numbers--much less predict the future (which is what you are trying to do).

And Jeremy posts these measures of the market's past performance without even knowing at first whether they are adjusted. Hard facts my ass.

Here are some hard facts for you Jeremy. If people want to invest their income in stock markets or bonds, they are perfectly free to do so. Last time I checked there are many private brokers willing to facilitate that. We don't need a government bureaucracy to oversee three hundred million individual funds.

Posted by Federico Campion on September 08th 11:30:11 AM

Frederico,

Obviously you didn't read the whole discussion, because the inflation numbers I referenced were to back up my assertion of stock market performance from 1887-1932 (the worst period in American history). They have nothing to do with my original argument.

At no time am I using past inflation numbers to predict future inflation numbers.

Do you see what's happened here? All of the numbers I used in my original analysis are inflation-adjusted projections by the Congressional Research Service. And nobody can find anything wrong with my analysis there - so we've moved the goalposts - and we're now quibbling about some random aside I mentioned about 1887-1932 stock market performance.

And if you do see an error in my reasoning, how about giving us some corrected numbers so we can set it straight rather than simply complaining about it? Anybody can complain...that doesn't make you right until you back it up with facts.

Posted by jeremy on September 09th 10:16:00 AM

You want to talk about moving goalposts? You haven’t addressed my broader critique, which is that you can’t use measures of past market performance in some arbitrarily chosen time period to predict future performance in some open-ended time period. This is intellectual sloppiness. Here’s why.

The entire privatization argument assumes that private accounts will make up for cuts in guaranteed benefits because stocks will unfailingly yield higher returns than bonds. Of course, the stock market entails higher risks for these higher returns, but privatization proponents cite the past performance of the stock market to argue that any future risk is minimal to non-existent.

It is true that we can take measures from arbitrarily chosen past periods to argue that stocks performed so reliably that they made up for the risk involved in dashing guaranteed benefits. However, to claim that this will hold for the future is tantamount to assuming that stock market returns are based on some kind of law of nature. In fact, in any market, stocks or otherwise, unusually high returns will be wrung out through competition. When you point out that the stock market has done well in the past, all you prove is that in the period you have chosen, stocks were under-priced. This doesn’t mean they will be under-priced in the future. Indeed, it could just as well mean they will be overpriced.

And in any case, we don’t have to rely on these kinds of fuzzy assumptions about past performance in order to forecast future performance. Economists have a measure for assessing how cheap (or costly) stocks are. Its called the price-earnings ratio.

And in fact, recent measures of the price-earnings ratio (price per share/company earnings per share) have born out the assumption that returns over the past century were produced by low prices. During the period from 1905-2005, the price-earnings ratio of the market averaged from about 14 to 16 depending on how you calculate it. The rate of return on the market from this period was 7%, actually about equal to the inverse of the price-earnings ratio (since if stocks costs more the rate of return is less). These days, the price-earnings ratio is about 20. This would give you around a 5 percent ballpark estimate for future returns. Not bad. But now lets introduce a little realism into the picture. What’s going to happen to this 5% politically? Is this really worth giving up the security of guaranteed benefits?

Well, its still a higher return than, say, the implicit real return on social security currently. But Jeremy, are you proposing that the private accounts be entirely invested in an index fund? Or just eighty percent? Or just sixty percent? If not, you will have to adjust your percentage return downward accordingly. Seventy percent in stocks would cut our five percent return down to about 4.1% (or so).

Then there are of course management fees. Jeremy downplayed these already by saying everyone will stick to index funds. I think the fee for an index fund is not going to be any lower than one percent especially when you introduce government bureaucracy, which will have to mediate this somehow. Let’s say management fees are at a half a percent (though in Britain they are 1.1%). Now we are down to 3.6% returns.

And who is to say that even if the funds are at first indexed, this will always hold? I mean, the forces behind the privatization movement—Wall Street lobbyists—certainly want to give account holders the option of riskier managed funds. At first, of course, accounts will be in indexed funds. But eventually, there will be an agitation to move to managed funds, with more pie in the sky predictions at how utopian everything will be and how everyone will be a millionaire. In practice, this will lead to a dissipation of already small returns into higher managements fees. Ka-ching for Wall Street managers. Risk for most people.

Let me ask you a question Jeremy. You call for indexed funds. Suppose SS was privatized—but then a few years from now people called for the introduction of managed funds in order to give account holders “choice”? Would you *oppose* the move to managed funds? I don’t think so. Be honest. Everyone knows where this is going. Look at Britain.

So now we are sitting pretty with a 3.6%, and that's assuming we have managed to protect the accounts from the political forces that will agitate for more expensive management fees and from the government bureaucracy that will have to be funded to negotiate the transition to private accounts. We are now outperforming social security by what--a whopping percentage point? In the meantime, we have introduced shitloads of risk. What kinds?

Well, market risks of course. But setting those aside (since Jeremy seems not to acknowledge that there is any risk in the market) what about the risk of these funds being endlessly politicized? As it stands, social security is still protected in Al Gore’s much-maligned lockbox. But once we shift to even indexed funds, the door is open politically for any amount of adjustments to the program. This factor alone takes away any security the accounts might offer, because it exposes them to endless politicizing. If you think the Wall Street lobby is going to stop at hitching private accounts to indexed funds, you are a fucking moron.

The bad faith of people like Jeremy is evident from their core argument. They claim that they support social security but that its just broken. Well, if that’s the case—why not call for fixing it by funding it so it can answer its current commitments?

To that, proponents of privatization offer extreme cynicism about the government’s ability to finance guaranteed benefits.

But if you don’t think the government can finance a guaranteed benefit, what makes you think that the government can oversee the transition to and the management of over three hundred million private stock portfolios? If you think guaranteed benefits are in danger of being drained by politicization, what makes you think that three hundred million private stock portfolios aren’t *also* in danger of politicization?

It doesn’t take a course in AP Calculus to see that this stuff doesn’t just unfold on some ideal x-y curve. Its politics. The New Deal had the wisdom to put it beyond politics to guarantee security. Privatizers want to expose it to politics because they say the gains are guaranteed. But this defeats the purpose of security. If you tunnel through Jeremy’s figures, you find that their sanguine predictions are based on intellectual sloppiness and the naive assumption that these accounts will someone be magically beyond politics.

I’ll say what I said before since Jeremy has no argument against it. If people want to invest their income in stock markets or bonds, they are perfectly free to do so. Last time I checked there are many private brokers willing to facilitate that. We don’t need a government bureaucracy to oversee three hundred million individual funds.

The point of the stock market is to take on risk for gains. The point of social security is to provide a safety net protected from market forces.

What’s so deplorable about having a small social safety net, when people can invest anything they want in the market through private brokers?

Posted by Federico Campion on September 09th 06:06:44 PM

By the way, the comments submission on this website is crap.

From your rhetoric, you act like you hold to some disinterested model of the public sphere. In fact, you pre-approve everything that goes up, and you only post it when you are going to respond to it immediately.

Just turn the spam filter off. Social Security is such a dead issue--and so uninteresting to most students--that you can practically hear the tumbleweed blowing through this url. I don't think any spammers are going to target you guys--and if they do, why not just manually delete that instead of manually approving every comment.

Posted by Federico Campion on September 10th 05:36:59 PM

Well, I certainly appreciate your advice, and I assure you that if it were that easy then I would have the comments fixed.

However, it seems that the spam filter we were using has malfunctioned and is marking everything as spam. Why not just turn it off? Well, I tried that but it seems that the settings page doesn't work anymore. And because i'm a volunteer and I have an actual job during the day, I don't have the 4 hours that it would take to scour the code and fix it.

So i'm having to actually go into our database and manually change the posts to "publish". And coincidentally, this usually happens when I have time to come back and reply.

No conspiracy here. I'll respond to your points when I have some time.

Posted by jeremy on September 11th 03:32:54 PM

"That easy"? I don't think I have ever been to a website where the comments button was "broken." This is not AP Calculus we are talking about here.

Posted by Federico Campion on September 13th 04:18:11 PM

Alright, you make a lot of points so i'll try to take them one at a time.

First you claim that my argument is "trying to predict future returns using past returns". I admit that this isn't an ideal arrangement. It sure would be nice to have a time machine and travel into the future to figure out what's going to happen.

However, we can't do that, so I'm doing the next best thing --using past stock market returns to give us *some idea* of future returns. And in fact, in my examples, I have used both recent and not so recent, both good and bad.

If we follow your argument, they why try to predict the future of anything? Why even have an OMB if, as you argue, nobody can predict the future? I just don't see that as helpful. And why even bother mentioning p/e ratios? If we can't predict the future, as you say, then what is the point in even bringing it up?

As for management fees, why not just agree to disagree? Since you're going to shoot my answer down with "nobody can predict the future based on past experiences", then all we have is me saying they will be low and you saying they will be high. I certainly can't argue from facts when the other party eschews all of the facts as irrelevant.

You also say:

"The bad faith of people like Jeremy is evident from their core argument. They claim that they support social security but that its just broken."

Well I think your side also argues in bad faith. Your claim that benefits are somehow "guaranteed" and that current SS funds are in Al Gore's "lockbox". These are both provably false.

First, SS benefits are guaranteed only so far as to say we are guaranteed not to get them. All predictions by the SS trustees (which I suppose you don't subscribe to because one can't predict the future) say that we'll start running a deficit in 2017. That means the current system is GUARANTEED not to be able to pay full benefits after that time without outside funding.

Second, the so called "trust fund" contains reciepts for money that has already been spend. There's no lockbox involved. Are you arguing that the money isn't really spent if we just keep a reciept?

Look, I can cite numbers all night, and you can keep dismissing them. But lets look at why i'm really pushing personal accounts.

It's not because of the return (but I think it will be better than the current system). It's because of the ownership. I don't like the government holding my money over me over and over, election after election, with the possibility that they might raise taxes or reduce my benefits. I just want to own my contributions. And you know what? Personally, if they offered me the option to put my SS contributions in a savings account earning 1% interest, i'd take it because it would be mine and the government couldn't take it away. At least i'd have that.

Right now all I have is the certainty that the current system can't pay what it's promised, and the only solution posited by your side is to raise taxes. Which means i'm going to pay even more into a system to get the same money out of it...when I don't even get a good return as it is? For god's sake, I can get a 5% return on an FDIC insured savings account these days. Does that bother you? If not, why not? I honestly would like to know.

So let's do this. Forget about investing PRAs in the stock market. How would you feel about changing social security so that your contributions are invested in Treasury bonds (not "special issue" treasury bonds that the supreme court ruled that I do not own). No more risk there, but now we have a true lockbox? Do you oppose this?

Posted by jeremy on September 14th 11:04:16 PM

Federico Campion,

We use past information all the time to determine future predictions and just for stocks. If you dont want to put your money in stocks you do not have to.

At your bank do you have a savings account? Do you like it? Why can we not have personal savings accounts through the government? I would rather use my Social Security number to count for my personal government retirement account as opposed to just an identification number. If we do not fix the current Social Security system, there will no be system.

I do not even care if I get 0% on my return as long as I got the money that is taken out of every paycheck and I believe with the current system I get beck a negative return on my dollar.

Would you put money in your savings account at the bank and when you want to take money out you have less then what you put into it? That is what is happening and what will ultimately happen with the current system.

Posted by Jason on September 15th 04:14:35 PM

|